Millions visit Pearl Harbor historic sites each year. Whether on the USS Arizona Memorial, walking down Cowpens Street toward the USS Missouri, or visiting the USS Oklahoma Memorial, visitors notice the quaint, abandoned homes hanging on to a corner neighborhood among overgrown trees and wondering what the people living there experienced. Or perhaps they wonder why these buildings are abandoned and allowed to fall apart. Here is their story in brief.

Building a Pacific Home

At the end of the Spanish-American War, the United States began investing in Pearl Harbor as a strategic naval base. After World War I, the U.S. turned its investments into a critical presence in the Pacific despite the tightening military budgets. The Rodman board, appointed in 1922 to study U.S. naval base requirements, prioritized the Ford Island Naval Air Station development and operation, even if budget cuts required closing mainland bases.1

As the U.S. built its forces, it also built homes for personnel assigned to Naval Air Station on Ford Island. First came barracks, and in 1923, they began building homes for military families. The Army began building its first homes as part of Luke Field. The Navy began building homes for officers’ families at Nob Hill and enlisted families at Belleau Wood Loop.2

Building Homes for Chief Petty Officers and their Families

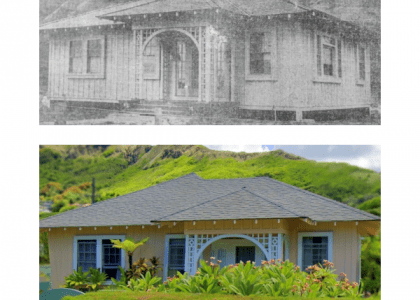

In 1923, the U.S. Navy began building six small bungalow-style houses for senior enlisted personnel, mainly Chief Petty Officers (CPOs), on the east end of Ford Island3 , which is near the USS Missouri and USS Oklahoma memorials are located today. Quarters 27 through 32 comprised an L-shaped CPO neighborhood along the south and east sides of the street that would later be named Belleau Wood Loop.4 Budgets were tight, so the Navy used local builders and incorporated Hawaii architecture.5 Senior enlisted personnel even helped out in their construction. Despite tightening budgets and the start of the depression, the Navy built four more quarters: Quarters 67 in 1928, Quarters 69 in 1931, Quarters 68 in 1932, and Quarters 70 (later renamed 90) in 1936.6

These were the first Ford Island homes explicitly constructed for families of senior enlisted personnel and among the first houses built for naval aviation personnel. In other words, they mark the place in time when air power was the latest technology for protecting a nation’s interests, whether with guns or surveillance. What’s unique about the Belleau Wood and nearby Nob Hill homes is that they were built for aviation-centered personnel but situated next to battleships, which by then were becoming antiquated.

The Significance of the Bungalow Style

Bungalows are typically single-story homes featuring low-pitched roofs and wide eaves, which aid ventilation in warm climates, especially before the advent of air conditioning. The term “bungalow” originated in Bengal, India, during the mid-1800s. These homes gained popularity in the 1800s when India was under British rule, as they were affordable and quick to construct, making them particularly suitable for British colonists and ambassadors. 7

In Hawaii, a company called Lewers & Cooke facilitated the rise of the bungalow home by importing affordable building materials and publishing home plans and bungalow homebuilding advice.

Lewers and Cooke promoted single-wall construction, which was ideal for Hawaii’s climate, where there was no insulation for heat or air conditioning because Hawaii homes typically had neither. “Board and Batten” construction provided more strength for the single walls than tongue and groove. Plus, exterior battens left smooth surfaces on the interior walls.9

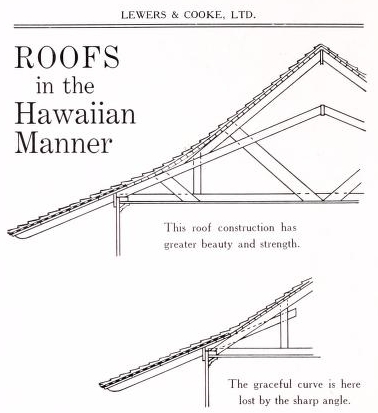

Lewers and Cooke also promoted using the “Hawaiian Manner” of roofs, which incorporates the ingenuity of a hip in roof construction. The top of the roof is built at a steeper angle to insulate against the sun and provide more space for hot air to rise. The second hip has a less steep angle to provide eaves with wider overhangs to shade windows and siding.10

The CPO Fourplexes

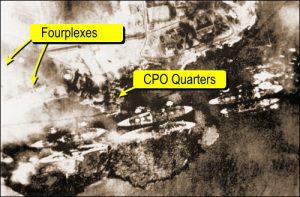

In the depths of the depression, the Navy continued its investment in Pearl Harbor and Ford Island. In 1932, the Navy proposed to build 18 buildings to house additional CPO families near the Belleau Wood Loop homes. They changed the plans for unknown reasons and built nine fourplexes, completed in 1939.13 Each of the nine two-story fourplexes housed four families. They were numbered Facility 45 through Facility 53.14

Ford Island Attacked on December 7, 1941

By the start of the 1940s, there were 45 homes in the Belleau Wood area of Ford Island where CPOs and their families enjoyed a peaceful, safe neighborhood. The children attended the Kenneth Whiting School, named after the Navy pilot who learned to fly from Orville Wright. The school was situated between the Belleau Wood homes and the Fourplexes and was surrounded by a grassy playground.15 Ford Island was only accessible by ferry.16 However, Ford Island had amenities that every child wanted: a pool, playgrounds, tennis courts, and backyards with battleships.

Sunday, December 7, 1941, started like any other morning. Eight-year-old Martin Anderson was “outside working on a miniature highway project” in his mother’s flower beds,” as he recalls.

Chief Petty Officer Warren Schott and his wife Betty woke up to sounds they had never heard before — and their bedroom window had a view of the Luke Field runway.

Next door, Fourteen-year-old Ralph Cote was lying on the sofa reading comics when he heard explosions just before 8 a.m. He dismissed them as dredging or construction noise until one explosion rolled him off the sofa.17

Edna Kelly jumped out of bed several hundred yards away and rushed into her two-year-old son Keoki’s room. He wasn’t there. “Where’s Keoki?” she asked her thirteen-year-old daughter Barbara.18

“He went outside,” Barbara answered.

Edna dashed outside, and Barbara went to their dining room window to see why her mother was in such a rush. She saw the stern of the USS California through the window, which was moored across the street just beyond the motor pool building. Then she saw a plane coming in low towards California’s bow and climbing as it approached. Barbara recalled, “When it was about half as high as the ship’s superstructure, it released its bomb.”

As the bomb fell on the California, she heard another plane to her left coming from Battleship Row. She watched the plane coming closer, flying what seemed like only feet from the ground. The pilot was only feet from their building, and she saw the pilot pulling back to avoid the aviation fuel tank several hundred yards from Barbara’s house. As the plane passed her, she saw the markings on the wings. She froze in shock for a few seconds. “We were being attacked!” she realized.

Meanwhile, Ralph managed to get his father out of bed to check out the planes flying overhead. His father couldn’t make sense of the scene and commented, “In 20 years in the Navy, that’s the most realistic drill I’ve ever seen.” And then, both Ralph and his father watched the bomb drop on the USS California, and they, too, had to quickly come to terms with the history and danger unfolding in their neighborhood.19

While the families in the fourplexes escaped into their basements, the families in the CPO bungalows hid wherever they could. Coty Burnfin gathered with other families in the schoolyard while Davalee Ledford and her mother Vada-Lee hid behind a wingback chair in Quarters 28.20 Yet no matter where they hid, they all felt the concussion when the USS Arizona’s magazines exploded — it rocked their homes, shook the ground, and left an indelible sound in their memories.

After the first wave of the attack, the families evacuated away from the battleships. Most went to the concrete bunker under Quarters K, Betty Schott and Kellys21 went to the supply building, and Ralph Cote went to the Bachelors Enlisted Quarters, used as emergency triage.22

The homes became a haven for the sailors escaping their sinking ships. After jumping overboard, the sailors had to swim through oil and fire to get to the shore, dodging strafing shrapnel and continued bombing. By the time they climbed onto Ford Island, they were covered in oil, burned, injured, and with very little clothing intact. Some took shelter under the bungalows until after the attack. Then, the homes provided the injured and oil-soaked emergency supplies: towels to wipe the oil off their eyes, clothes where theirs were soaked or burned, and even Betty Schott’s kitchen curtains when they ran out of clothes and towels.

The attack itself was only the beginning of the darkest times for these families. The fires continued to burn on Battleship Row, so families were not allowed to return to their homes for days. Instead, they spent sleepless nights crowded into the bachelor officers’ quarters, wondering if their husbands and fathers were alive and listening to the constant anti-aircraft fire outside. For those who were reunited, it would be briefly. Almost none of them could live in their Ford Island homes again, even if they had wanted to. Children and wives were evacuated to the mainland within a month, and they stayed on the mainland while their husbands and fathers went to war.

Demolition of the Historic Homes on Ford Island

The Navy demolished first bungalows in 1942 as part of the effort to right the capsized USS Oklahoma, which required a series of winches based on the land beneath Quarters 27 and 67. 23 Between 1942 and 1945, Quarters 30 was moved to Langley Avenue in the nearby Nob Hill neighborhood.24 By 1978, the Navy demolished the CPO Four-plexes. Studies of the area suggest they were demolished because they were built on a landfilled area.25

A 1987 survey of military homes commissioned by the US military recommended it for demolition and removal from the housing inventory because it “did not meet the minimum net square footage for US Army family housing.”26

In the 1990s, the last family moved out of the Belleau Loop Bungalows and the other CPO Bungalows on Belleau Wood Loop.27 They sat vacant without maintenance for over a decade and in 2005, the Historic Hawaii Foundation named the CPO Quarters on Ford Island to Honolulu Magazine’s Most Endangered Historic Sites.28 Some relief came when they were designated as part of the Pearl Harbor National Memorial by a Presidential Proclamation in 2008. This proclamation paved the way for the National Park Service to take over their management and care.

From 2009 through 2012, the National Park Service provided emergency care, such as fumigating for termites and stabilizing the structural foundations.29 In 2015, the National Park Service demolished Quarters 28 and constructed a new structure in its place.30 Quarters 31 and Quarters 32 remain in poor condition, with vegetation overwhelming their wood construction. Quarters 29 and 90 appear to be in better condition than Quarters 31 and 32. Quarters 30 is now located in Nob Hill, a home designated for junior officers and their families.

Ford Island CPO Quarters Today

As of 2024, 39 of the 45 enlisted family homes that stood on December 7, 1941, have been demolished. Situated in the shadow of battleships, these houses suffered damage from shrapnel, oil, and fire during and after the attack.31 Yet, they all survived 1941, but they did not escape the 1970s.

The six remaining bungalows (Quarters 90, 29, 30, 31, 32, 68) comprise the only remaining historic neighborhood built for senior enlisted Navy personnel at Pearl Harbor.32 Five remain unused and endangered. As more Pearl Harbor survivors pass away each year, these houses remain our few tangible witnesses connecting us to the dark day in history.