In the 1950s, Lanikai shifted from being a beach getaway filled with second homes for the wealthy to a neighborhood of full-time residents. There are three historic houses of this era on the historic register: the Boyen home, the Clarence Cooke home, and the Wrenn beach cottage.

Heaton L. Wrenn and Caroline Cooke Wrenn

Heaton Luse Wrenn (1900–1978) and his wife, Carolene Cooke Wrenn (1905–1987), were prominent figures in Honolulu society during the early to mid-20th century. Their lives and backgrounds are intertwined with Hawaii’s history, particularly through family connections and community contributions.

Heaton was born in San Francisco in 1900. He graduated from Stanford Law School in 1923. In 1924, Heaton moved to Hawaii to begin practicing law. He initially worked on the Big Island before joining the law practice of James Coke, a former Territorial Supreme Court Chief Justice. He became a partner in Anderson, Wrenn & Jenks (later Goodsill, Anderson, Quinn & Stifel). His legal expertise led to roles on the boards of prominent Hawaiian companies, including Hawaiian Electric, C. Brewer, and Consolidated Amusement. Heaton also served as president of the Bar Association of Hawaii and the Honolulu Symphony Society. He gained respect for defending the Institute of Pacific Relations against accusations by Senator Joseph McCarthy during the 1950s.

Caroline was the daughter of C. Montague Cooke Jr. and Sophie Boyd Cooke, members of the prominent Cooke family in Hawaii. Her father, C. Montague Cooke Jr., was a noted scientist and philanthropist, contributing significantly to Hawaii’s educational and cultural institutions.

Caroline married Heaton Wrenn in 1927. The couple became deeply involved in Honolulu society, reflecting the Cooke family’s legacy and Heaton’s professional accomplishments.

The Story of the Wrenn Beach Cottage

Early Beginnings: 1931

In December 1931, the Wrenns purchased two beachfront lots adjacent to Caroline’s parents in the newly developed Lanikai subdivision. The area had been recently transformed into a residential community marketed as a serene beach retreat for Honolulu’s affluent residents. Caroline’s parents owned a neighboring property, further anchoring the family’s ties to Lanikai.

Construction of the Cottage: 1935

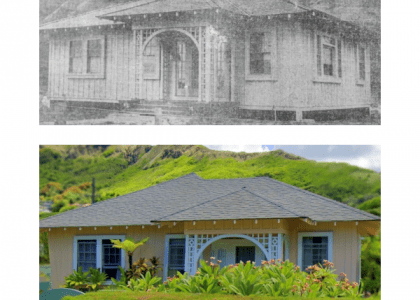

By 1935, the Wrenns constructed a single-story beach cottage at 1038 Mokulua Drive for $6,000. The home, embodying the Plantation Modern architectural style, included features such as a hipped roof with overhanging eaves, single-wall construction using tongue-and-groove wooden panels, and expansive windows to take advantage of natural light and ventilation. The home was designed for both relaxation and functionality, incorporating an open living room with a high-beam ceiling and a butler’s pantry in the kitchen, which featured original cabinetry with glass knobs.

Expansion: 1939

As the Wrenn family grew, the cottage was expanded with a second story in 1939. The design emphasized simplicity and clean lines while incorporating modernist elements. Notable features included cantilevered sections of the second floor supported by decorative brackets, a recessed light beam between the living and dining areas, and a sleek railing on the interior staircase. These design choices reflected the broader architectural trends of the 1930s, particularly the growing popularity of modernism in Hawaii.

Ownership Changes and Later Years

In 1958, the Wrenns sold the property to Cecil V. Augustine, who sold it a year later to Clifton and Daisy Weaver. The Weavers made the cottage their primary residence, which has remained in their family ever since. Clifton Weaver, a co-founder of the Spencecliff restaurant chain, further solidified the home’s status as a cherished family retreat.

Plantation Modern Design and Why it Matters

When I see photos of people with big, permed hair or a mullet, it reminds me of a time in the 1980s in an authentic way that I wouldn’t at a costume party.

Similarly, a building’s style can remind us of the period in which they were built. Owners often want their properties to look younger, so they demolish, remove, cover, and remodel the styles to reflect a different style, much like a new haircut.

With each passing year, there are remodels, demolitions, “upgrades,s” and additions to homes until now, a hundred years later,r there are only a handful of the originals left. This is the case in Lanikai.

There are so few homes left in Lanikai that, over the years, they didn’t gut their original features intentionally or through natural deterioration. The Wrenn beach cottage is one of those rare survivors that can take us back to the 1930s thanks to its Planation Modern design. The Plantation Modern style marks an era when homes still kept plantation-style features but added more modern touches.

Plantation style:

- Single-wall construction: A hallmark of plantation-style homes, this method uses tongue-and-groove wooden walls, which are lightweight and suitable for Hawaii’s climate.

- Low-pitched, hipped roofs: These help shed rain and provide shade, essential for tropical weather.

- Wide overhanging eaves: Designed to protect against sun and rain.

- Lanais (porches): Open spaces that encourage indoor-outdoor living, a feature of traditional Hawaiian homes and plantation architecture.

Modern Touches:

- Clean lines and rare unnecessary decorations.

- Large, unadorned windows: Allowing natural light and ventilation

- Bringing indoor and outdoor spaces together using open floor plans and easy connections to gardens or patios.

Architectural and Historical Significance

Today, the Wrenn Beach Cottage is recognized on the Hawaii State Register of Historic Places for its architectural and historical value. It exemplifies the early development of Lanikai as a beachside community and showcases how Hawaiian architects adapted modernist principles to fit the local environment. The home’s design, materials, and craftsmanship reflect its time of construction and its enduring relevance as a part of Hawaii’s architectural heritage.

Sources

Hibbard, D. (2016). Heaton L. And Caroline Cooke Wrenn Beach House [Nomination for the Hawaii State Register of Historic Places]. DLNR Hawaii. dlnr.hawaii.gov