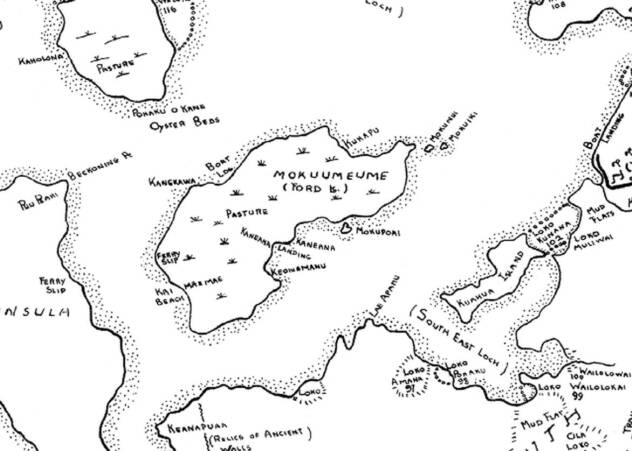

Two caldera volcanoes—today known as the Waianae and Koolau mountains—and subsequent erosion formed the island of Oahu. As the oceans receded, the once-submerged coral reef became the foundation for the island’s plains. Mountain streams flowed through the center of these plains via three rivers that converged to carve out a single valley in the coral. When the ocean level rose again, these three rivers and the resulting wide, shallow channel formed what we know today as Pearl Harbor.1

The Hawaiians, with their deep connection to the land, named Pearl Harbor “Wai Momi,” which refers to “pearl water,” and “Pu‘uloa,” which refers to “long hill.” These names, steeped in history and culture, reflect the Hawaiians’ reverence for the land and water. They used the harbor as a food source through an extensive network of fishponds that fed the population for centuries. Its plentiful oysters eventually gave the harbor its name.2

Hawks Encircle Pearl Harbor

In 1778, British explorer Captain James Cook became the first European to sail to the Hawaiian Islands.7 Foreign interest in Pearl Harbor took root soon after. However, the harbor’s shallow coral entrance hindered its development as a port for foreign ships for over a hundred years.

In the late 1790s, Captain George Vancouver of the British Royal Navy attempted to sail into the harbor, but the shallow coral entry prevented him from doing so.8 In 1840, U.S. Navy Commodore Charles Wilkes surveyed the harbor and noted, “If the water upon the bar should be deepened, which I doubt not can be effected, it would afford the best and most capacious harbor in the Pacific.”9

In a secret report to the Secretary of War in 1873, U.S. Major General Schofield and Lt. Col. B.S. Alexander stated, “If this coral barrier were removed, Pearl Harbor would seem to have all the necessary properties to enable it to be converted into a good harbor of refuge.”10

By 1875, the Kingdom of Hawaii signed a reciprocity treaty with the U.S., granting land in Puuloa (what is now known as Pearl Harbor) in exchange for allowing Hawaiian merchants to sell sugar and other products to the U.S. tariff-free.11

By 1875, the Kingdom of Hawaii signed a reciprocity treaty with the U.S., granting land in Puuloa (what is now known as Pearl Harbor) in exchange for allowing Hawaiian merchants to sell sugar and other products to the U.S. tariff-free.12 In 1887, the U.S. gained exclusive rights to Pearl Harbor.13

On January 17, 1893, a committee of seven foreigners, backed by the U.S. Marines, overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom to form the Republic of Hawaii, which was eventually annexed by the United States in 1898.14

Meanwhile, Ford Island was still privately owned by the I‘i estate. In 1899, the estate began leasing part of the island to the Oahu Sugar Company for sugar cultivation, which was made feasible by adding the island’s first artesian well.15

Following the Spanish-American War, the U.S. recognized the strategic importance of Pearl Harbor as a military location for a deep-water harbor. The decision to invest in this location was not taken lightly. In 1900, the U.S. Navy started dredging the harbor to a depth of 35 feet and 600 feet wide to accommodate naval ships.16

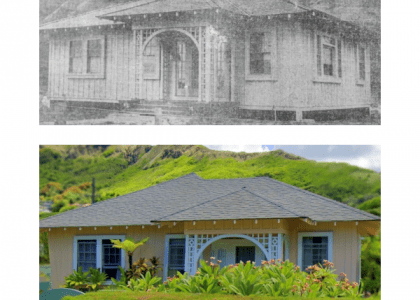

With the obstacle of the shallow harbor entrance now cleared, military construction accelerated. The U.S. acquired additional land around the harbor in 1901 and appropriated $6.2 million for ongoing dredging and the construction of naval facilities.17 In 1902, the U.S. purchased 25 acres on the south end of Ford Island, followed by further acquisitions in 1915. Finally, in 1916, the U.S. purchased the remainder of Ford Island from the I‘i estate18, ushering in an unprecedented build-up of military construction in Hawaii and setting the stage for the site of the United States’ entry into World War II.

- Owen, W. (2000). Over Hawaii. Fog City Press. ↩︎

- Minatodani, D. (n.d.). Research Guides: Chronicling America: Historic Newspapers from Hawaiʻi and the U.S.: Pearl Harbor. Retrieved October 28, 2024, from https://guides.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/c.php?g=105252&p=687130 ↩︎

- Dorrance, W. H. (1991, December 19). Moku‘ume‘ume. Historic Hawaii Foundation News. ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎

- Ford, E. R. (1916). Ford Genealogy: Being an Account of the Fords who Were Early Settlers in New England. More Particularly a Record of the Descendants of Martin-Mathew Ford of Bradford, Essex Co., Mass. The author. ↩︎

- Germano, V. G., Melnick, R. Z., & Six, H. (2020). CULTURAL LANDSCAPE REPORT FOR FORD ISLAND CPO BUNGALOWS NEIGHBORHOOD AND BATTLESHIP ROW. National Park Service. ↩︎

- James Cook. (2024). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=James_Cook&oldid=1247980872#cite_note-Collingridge_2003_380-59 ↩︎

- Minatodani, n.d. ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎

- Honolulu, P. H. N. M. & US H. 96818 P. 808 422-3399 C. (n.d.). Pearl Harbor—Pearl Harbor National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service). Retrieved October 28, 2024, from https://www.nps.gov/valr/learn/historyculture/pearl-harbor.htm ↩︎

- Nakamura, K. (2024, April 17). Hawaii’s Long Road to Becoming America’s 50th State. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/news/hawaii-50th-state-1959 ↩︎

- Germano et al., 2020 ↩︎

- Honolulu & Us, n.d. ↩︎

- Minatodani, n.d. ↩︎

- Germano et al., 2020 ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎